Introductory R

Welcome to programming in R! This module will serve as a tutorial to help you get acquainted with the R programming environment, and get you started with some basic tools and information to help along the way. We won’t follow this internet module to the letter in our time together, but we will discuss the same topics, and in about the same order. Hopefully, this tutorial will be helpful in either preparing you for the workshop or for revisiting important concepts after the workshop.

Like any language, the learning curve for R is steep (like a cliff, not a hill), but once you get the hang of it you can learn a lot quickly. Cheat sheets like the tutorial from the workshop (or these) can help you along the way by serving as handy references.

Working with code

We will spend a bit of time during the introductory session to orient attendees with the RStudio IDE and talk about file management. Here are some additional pointers about working with code.

There are a lot of different ways to write computer code. Each has pros and cons and all of them are intended to increase efficiency and readability. There is no “right” way to edit your code, but it will make your life easier if you find a style you like and stick to those conventions. Here are a couple of points that can be helpful when you are just starting out:

Commenting code is helpful

# This is a comment.

# We know because it is preceded

# by a hashtag, or 'octothorpe'.

# R ignores comments so you have

# a way to write down what you have

# done or what you are doing.

# This is useful for sharing

# code or just figuring out

# what you did.There are a few ways to run code:

Click on a line of code and press

Ctrl + Enter.Highlight a chunk of code and do the same.

Either 1 or 2, but press the

Runbutton at the top of the source file to run the code block.Once you’ve run a code block you can change it and then press the button next to

Run(orCtrl + Shift + P) to ‘re-run’ the previous block of code.

Try it on your own!

Type the following line of code into a blank source file, and run it using one of the methods above.

# Add 1 and 1 together

1 + 1

[1] 2Some stricter R programming rules:

All code is in R is case sensitive.

# Example (run the following lines):

a <- 1

A <- 2

# Are these two things equal?

a == A

[1] FALSEWe have few things going on above.

We’ve defined a couple of objects for the first time. You do this by assigning the value on the right of the arrow to the variable on the left. We can use the assignment arrow

<-or an equal sign=. The former is preferred, but for our purposes it will make absolutely no difference, and=is faster to type than<-until you know your speed-key combinations.The

==that we typed is a logical test that checks to see if the two objects are identical. If they were, then R would have returned aTRUEinstead ofFALSE. This operator is very useful, and is common to a number of programming languages.Note in the output that the two objects are not the same, and R knows this when we test to see.

You can’t start an object name with a number, but you can end it with one.

# This won't work

1a <- 1

# But this one works

# Try it by typing

# a1,

# print(a) or

# show(a)

# in the console:

a1 <- 1R will overwrite objects sequentially, so don’t name two things the

same unless you don’t need the first. Even then it is risky business. In

the example below, our object a takes on the second value

provided and the first is lost.

a <- 1

a <- 2

a

[1] 2Some things can be expressed in multiple ways. For example, both

“T” and “TRUE” can be used to indicate a

logical value of TRUE.

T == TRUE

[1] TRUESome names are reserved or pre-defined. Did you notice that R already

knew what T and TRUE were without us defining

them? These reserved operators, and built in functions

are the building blocks of the R language.

For example,

in, if, else, for, function()…and a mess of others have special uses. If it is not obvious already, we should avoid using these words to name objects that we define in our source files.

Some symbols are also reserved for special use as operators, like:

+, -, *, /, % %, &, |, <, >, (, {, [, '', "", ...…and a bunch of others.

Some other handy tricks

The Home button will move you to the start of the line

of code, and to the start of the line if you press it twice. The

End button on your keyboard will take you to the end of a

line. These will help you move around your code faster.

The Tab button on your keyboard will move the code to

the right some number of spaces (user defined). Pressing

Shift + Tab will move code to the left. These can help you

organize your code quickly.

A single click of the mouse will move the cursor into position. Double-click will highlight the word you are clicking, and a triple left-click will highlight an entire line.

Use search and replace functionality to copy big chunks of code and

change names as needed. You can also use this to just search your code.

Press Ctrl + F to open the sub menu at the top. When code

gets so redundant that you copy and paste the same code several times,

you are probably better off writing a function that you can use whenever

you like.

Functions are the life blood

Functions make R what it is. These are all of the “commands” that are available to a user through the base software, or through packages that can be added on. When you can’t find the function you need, you can write one to do it (eventually). At their most basic level, functions do stuff to objects in R. This is what makes R both a functional programming language and an object-oriented programming language.

Data structures and manipulation

Vectors

Despite the wide range of uses you hear about, R is a statistical programming language at its core. It is not a mathematical language or a general programming language, although it has a lot of functionality outside this original scope. R is what is known as a “high-level” or “interpreted” language. This means the pieces that make it up are a little more intuitive to the average user than low-level languages like C or C++. The back-end of R is, in fact, a collection of low-level code that builds up the functionality that we need. Because anyone can write new functions for R, it has a broad range of uses, from data management to math, and even GIS and data visualization tools, all of which are conveniently wrapped in an “intuitive”, “user-friendly” language.

Part of this flexibility comes from the fact that R is also a “vectorized” language. Why do you care about that? This will help you wrap your head around how objects are created and stored in R, which will help you understand how to make, access, modify, and combine the data that you will need for any approach to data analysis.

Let’s take a look at how this works and why it matters. Here, we have

defined an object, a, as a variable with the value of

1…or have we?

a <- 1

a

[1] 1What is the square bracket in the output here? It’s an index. The

index is telling us that the first element of a is

1. This means that a is actually a “vector”,

not a “scalar” or singular value. You can think of a vector as a column

in a spreadsheet or a data table. By treating every variable as a

vector, or an element thereof, the language becomes much more

general.

So, even if we define something with a single value, it is still just a vector with one element. For us, this is important because of the way that it lets us do math. It makes vector operations so easy that we don’t even need to think about them when we start to make statistical models. It makes working through the math a zillion times easier than on paper! In terms of programming, it can make a lot of things easier, too.

The vector is the basic unit of information in R. Pretty much everything else is either made of vectors, or can be contained within one. Wow, what an existential paradox that is. Let’s play with some:

Atomic vectors

A vector that can hold one and only one kind of data:

- Character

- Numeric

- Integer

- Logical

- Factor

- Date/time

And some others, but none with which we’ll concern ourselves.

Below are some examples of atomic vectors. Run the code

to see what it does:

Integers and numerics

a <- c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5) # Make a vector of integers 1-5

print(a) # One way to look at our vector

[1] 1 2 3 4 5show(a) # Another way to look at it

[1] 1 2 3 4 5a # A third way to look at it

[1] 1 2 3 4 5str(a) # Look at the structure, integer class

num [1:5] 1 2 3 4 5Here is another way to make the same vector, but we need to pay

attention to how R sees the data type. A closer look shows that these

methods produce a numeric vector (num)

instead of an integer vector (int). For

the most part, this one won’t make a huge difference, but it can become

important when writing statistical models.

# Define the same vector using a sequence

a <- seq(from = 1, to = 5, by = 1)

str(a)

num [1:5] 1 2 3 4 5Characters and factors

Characters are anything that is represented as text strings.

b <- c("a", "b", "c", "d", "e") # Make a character vector

b # Print it to the console

[1] "a" "b" "c" "d" "e"str(b) # Now it's a character vector

chr [1:5] "a" "b" "c" "d" "e"b <- as.factor(b) # But we can change if we want

b

[1] a b c d e

Levels: a b c d estr(b) # Look at the data structure

Factor w/ 5 levels "a","b","c","d",..: 1 2 3 4 5Factors are a special kind of data type in R that we may run across from time to time. They have levels that can be ordered numerically. This is not important except that it becomes useful for coding variables used in statistical models- R does most of this behind the scenes and we won’t have to worry about it for the most part. In fact, in a lot of cases we will want to change factors to numerics or characters so they are easier to manipulate.

This is what it looks like when we code a factor as number:

as.numeric(b)

# What did that do?

?as.numericAside: we can ask R what functions mean by adding a question mark as we do above. And not just functions: we can ask it about pretty much any built-in object. The help pages take a little getting used to, but once you get the hang of it…in the mean time, the internet is your friend and you will find a multitude of online groups and forums with a quick search.

Logical vectors

Most of the logicals we deal with are yes/no or comparisons to

determine whether a given piece of information matches a condition.

Here, we use a logical check to see if the object a we

created earlier is the same as object b. If we store the

results of this logical check to a new vector c, we get a

new logical vector of TRUE and FALSE.

# The '==' compares the numeric vector to the factor one

c <- a == b

c

[1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSEstr(c)

logi [1:5] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSEWe now have a logical vector. For the sake of demonstration, we could

perform any number of logical checks on a vector (it does not need to be

a logical like c above).

is.na(a) # We can check for missing values

[1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSEis.finite(a) # We can make sure that all values are finite

[1] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE!is.na(a) # The exclamation point means 'not'

[1] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUEa == 3 # We can see if specific elements meet a criterion

[1] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSEunique(b) # We can just look at unique values

[1] a b c d e

Levels: a b c d eThe examples above are all fairly simple vector operations. These form the basis for data manipulation and analysis in R.

Vector operations

A lot of data manipulation in R is based on logical checks like the ones shown above. We can take these one step further to actually perform what one might think of as a query.

For example, we can reference specific elements of vectors directly.

Here, we specify that we want to print the third element of

a.

# This one just prints it

a[3]

[1] 3# This one stores it in a new object

f <- a[3]Important

If it is not yet obvious, we have to assign the output of functions

to new objects for the values to be useable in the future. In the

example above, a is never actually changed. This

is a common source of confusion early on.

Going further, we could select vector elements based on some

condition. On the first line of code, we tell R to show us the indices

of the elements in vector b that match the character string

c. Outloud, we would say, “b where the value

of b is equal to c” in the first example. We

can also use built-in R functions to just store the indices for all

elements of b where b is equal to the

character string ‘c’.

b[b == "c"]

[1] c

Levels: a b c d ewhich(b == "c")

[1] 3Perhaps more practically speaking, we can do elemen-twise math operations on vectors easily in R.

a * .5 # Multiplication

[1] 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5a + 100 # Addition

[1] 101 102 103 104 105a - 3 # Subtraction

[1] -2 -1 0 1 2a / 2 # Division

[1] 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5a^2 # Exponentiation

[1] 1 4 9 16 25exp(a) # This is the same as 'e to the...'

[1] 2.718282 7.389056 20.085537 54.598150 148.413159log(a) # Natural logarithm

[1] 0.0000000 0.6931472 1.0986123 1.3862944 1.6094379log10(a) # Log base 10

[1] 0.0000000 0.3010300 0.4771213 0.6020600 0.6989700We can also do string manipulation really easily:

b <- as.character(b)

paste(b, "AAAA", sep = "") # We can append text

[1] "aAAAA" "bAAAA" "cAAAA" "dAAAA" "eAAAA"paste("AAAA", b, sep = "") # We can do it the other way

[1] "AAAAa" "AAAAb" "AAAAc" "AAAAd" "AAAAe"paste("AAAA", b, sep = "--") # Add symbols to separate

[1] "AAAA--a" "AAAA--b" "AAAA--c" "AAAA--d" "AAAA--e"gsub(pattern = "c", replacement = "AAAA", b) # We can replace text

[1] "a" "b" "AAAA" "d" "e" e <- paste("AAAA", b, sep = "") # Make a new object

e # Print to console

[1] "AAAAa" "AAAAb" "AAAAc" "AAAAd" "AAAAe"substr(e, start = 5, stop = 5) # We can strip text (or dates, or times, etc.)

[1] "a" "b" "c" "d" "e"We can check how many elements are in a vector.

length(a) # A has a length of 5, try it and check it

[1] 5a # Yup, looks about right

[1] 1 2 3 4 5And we can do lots of other nifty things like this.

Matrices

Matrices are rectangular objects that we can think of as being made up of vectors.

We can make matrices by binding vectors that already exist

cbind(a, e)

a e

[1,] "1" "AAAAa"

[2,] "2" "AAAAb"

[3,] "3" "AAAAc"

[4,] "4" "AAAAd"

[5,] "5" "AAAAe"Or we can make an empty one to fill.

matrix(0, nrow = 3, ncol = 4)

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 0 0 0 0

[2,] 0 0 0 0

[3,] 0 0 0 0Or we can make one from scratch.

mat <- matrix(seq(1, 12), ncol = 3, nrow = 4)We can do all of the things we did with vectors to matrices, but now we have more than one column, and official ‘rows’ that we can also use to these ends:

ncol(mat) # Number of columns

[1] 3nrow(mat) # Number of rows

[1] 4length(mat) # Total number of entries

[1] 12mat[2, 3] # Value of row 2, column 3

[1] 10str(mat)

int [1:4, 1:3] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ...See how number of rows and columns is defined in data structure? With rows and columns, we can assign column names and row names.

colnames(mat) <- c("first", "second", "third")

rownames(mat) <- c("This", "is", "a", "matrix")

mat

first second third

This 1 5 9

is 2 6 10

a 3 7 11

matrix 4 8 12str(mat) # Take a look to understand

int [1:4, 1:3] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ...

- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

..$ : chr [1:4] "This" "is" "a" "matrix"

..$ : chr [1:3] "first" "second" "third"All the same operations we did on vectors above…one example.

More on matrices as we need them. We won’t use these a lot in this module, but R relies heavily on matrices (and arrays) to do the heavy lifting behind the scenes.

Dataframes

Dataframes are like matrices, only not. They have a row/column structure like matrices. But, they can hold more than one data type! They are basically a whole bunch of vectors that are smashed together into a single container.

Referencing specific elements of a dataframe is similar to a matrix,

but we can also access columns (“variables”) by name using the

$ to reference the column we want from within a dataframe.

We’ll look at this with some real data so it’s more fun. Most of the

packages in R have built-in data sets that we can use for examples, too.

For now, let’s read in our first real data file as most of our data are

stored that way and will be read in as .csv or

.txt files.

Lists

We won’t talk about lists for this workshop, but it is important that you’ve heard of them because most of the down-and-dirty, real programming in R relies heavily on lists. Lists are a special kind of vector that can hold multiple data types. Those data types can even be different types of objects, like vectors, dataframes, matrices, or even other lists! Loosely speaking, your workspace even functions as a special kind of list that contains each of the things you’ve created. It’s lists all the way down, people.

Loading data from files

First, we need to make sure that the data are in a place where R can

access them. One way to do this is to hard-code the file path (e.g.,

setwd("C:/Users/.../physical.csv")), but that makes it a

pain when you hand off code or reorganize computer files. I usually just

make sure that my data and my code are in the same directory on my

computer if I am working on an analysis of some sort (or writing a

website in this case). Then, we can set the working directory

in R to that folder using any number of different options. My

preferences is to either work out of R projects, or to use

Session > Set Working Directory > To Source File Location.

Next, we have to assign our data to a new object, or R will just dump

it to the console and it won’t be stored in our

Environment. In this case, I am going to give my data a

meaningful name based on the lake from which they were collected.

Finally, we have to tell R how to read the file and what the name of the file is.

otsego <- read.csv("data/physical.csv")If it looks like nothing happened, then it probably worked. Have a

look at your Environment tab to make sure it is there (mine

is bottom left, yours may be elsewhere depending on how you set up your

pane layout).

You can also look at whether it is included in the Environment like this:

ls()Data summaries

Now that we have some real data, let’s break it down a little bit. Go ahead and give these a try to see what kind of information they each give you about the data set.

ls() # We can use ls() to see what is in our environment

head(otsego) # Look at the first six rows of data in the object

nrow(otsego) # How many rows does it have?

ncol(otsego) # How many columns?

names(otsego) # What are the column names?

str(otsego) # Have a look at the data structure

summary(otsego) # Summarize the variables in the dataframeNow let’s look at some specific things.

What is the value in 12th row of the 4th column of

otsego? Notice that we have two indices now. That is

because we have both rows (first dimension) and columns (second

dimension) in our data set now!

otsego[12, 4]

[1] 14Another way to say this is, “What is the 12th value of

depth in otsego”?

otsego[12, "depth"]

[1] 14More realistically, we might want to know the average temperature

(temp) at a given depth in the lake. In the

example below, we ask R for the mean temperature at 10 m across all

observations (rows). Notice that now we are back to a single dimension

inside our index brackets [] because the column

temp is an atomic vector inside of otsego. The

dollar sign ($) here is telling R to look for something

called temp inside of the otsego

dataframe.

mean(otsego$temp[otsego$depth == 10.0], na.rm = TRUE)

[1] 10.7102Wow…heavy stuff, but this is how the wheels turn.

Let’s look at a better way to summarize these data by year. To do

this, we’ll load the tidyverse package. This is actually a

collection of packages designed to improve logical flow and presentation

of data manipulation (so we don’t have to use $ and

[ ] all the time because that’s hard to read!!).

Better data summaries

We’ll quickly demonstrate a very useful data summary pipeline that is

supported by a couple of different packages from the

tidyverse, so I am going to load the whole suite at once.

You will need to install this first using

install.packages("tidyverse") or one of the techniques

demonstrated in live and recorded content.

library(tidyverse)You will probably get a bunch of messages to tell you which packages

have been loaded and if there were any NAMESPACE conflicts

of functions that are “masked” from base R. None of these will affect

us. I just told R not to print it on the website.

Now that we’ve loaded this suite of data management tools, we can summarize temperature in our data set really easily.

First, we will group the data set by month and depth so that behind the scenes R knows this is our grouping structure:

otsego <- group_by(otsego, month, depth)Note that this changes otsego into a

tibble, which is basically just a fancy dataframe with

attributes like Groups.

Now, we can summarize temperature by depth in each month across years:

otsego_summary <- summarize(otsego, mean_temp = mean(temp), sd_temp = sd(temp))You’ll get a message here to let you know that summarise

is using the grouping structure that you had previously specified, and

it is sorting by month.

If you print your new object, you’ll see that it has four columns:

month, depth, mean_temp, and

sd_temp.

print(otsego_summary)

# A tibble: 284 × 4

# Groups: month [12]

month depth mean_temp sd_temp

<int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 1 0 0.93 NA

2 1 0.1 1.79 1.36

3 1 2 2.10 1.07

4 1 4 2.12 0.988

5 1 6 2.25 0.962

6 1 8 2.37 0.908

7 1 10 2.39 0.880

8 1 12 2.5 0.860

9 1 14 2.52 0.813

10 1 16 2.60 0.813

# … with 274 more rowsAs a teaser for after the break, we could make a quick scatterplot

using ggplot() as long as we have the

tidyverse loaded!

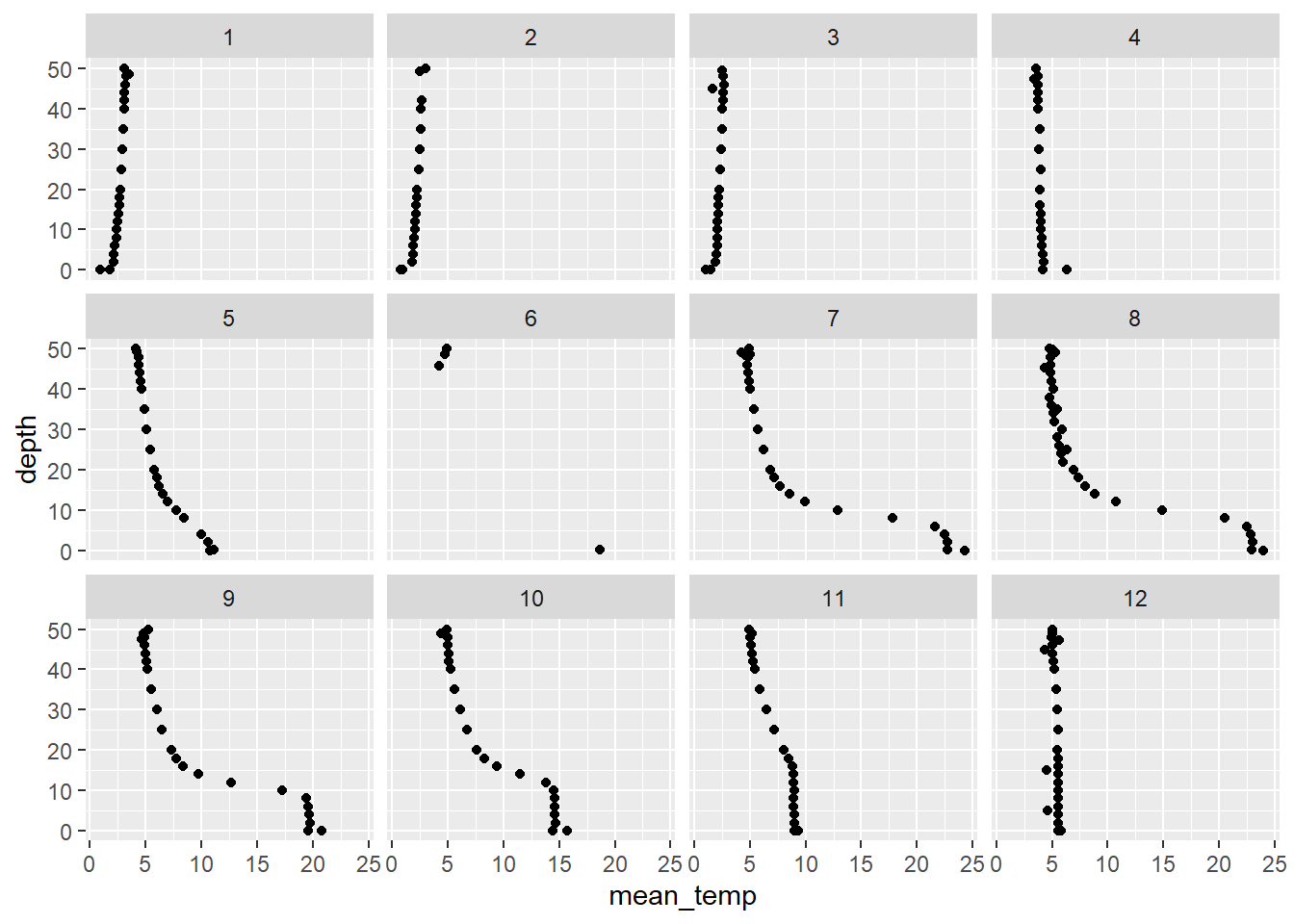

ggplot(otsego_summary, aes(x = mean_temp, y = depth)) +

geom_point() +

facet_wrap(~month)

Wow, what a neat picture, but what if we wanted temperature in Fahrenheit for our stakeholders???

Creating new variables

So, what if we wanted to do something like convert temperature from Celcius to Fahrenheit? We could make a function to do this for us:

# Define a function to convert temperature

# in celcius to temperature in farenheit:

cToF <- function(cels) {

faren <- cels * (9 / 5) + 32

return(faren)

}And then we can use it to create a new variable in the

otsego dataframe, which I have named tempF.

This variable (column) is created inside otsego

automatically.

# Test the function out.

# Here, we create a new variable in the

# otsego dataframe to hold the result

otsego$tempF <- cToF(otsego$temp)Now that we have our new column, we may wish to write this back out to a file so we can share it with our collaborators (who for some reason need temperature measured on the Fahrenheit scale?).

There are a couple of ways to do this.

First, we could just use the write.csv function. This

one is pretty limited in terms of options, but that also makes it easy

to use. We just need to tell R what the object is that we want to write

to a csv file and what the name of the file will be. Do be careful

because this will overwrite existing files with the same name without

asking if that is okay.

write.csv(x = otsego, file = "physicalF.csv")I like a little more flexibility in the file write process, so I

usually use the write.table function. This can be used to

achieve the same end depending on options, but allows other options like

ommitting row.names from the output file. Here is an

example of how it works:

# Write the data set to a csv file.

# We specify the object, the filename, and

# we tell R we don't want rownames or quotes

# around character strings. Finally, we tell

# R to separate columns using a comma.

# We could do exactly the same thing, but use a ".txt"

# file extensions, and we would get a comma-separated

# text file if we needed one.

write.table(

x = otsego, file = "physicalF.csv", row.names = FALSE,

quote = FALSE, sep = ","

)A third way to write objects from R to a file is by saving it as an R

data file (.rda extension). This comes in handy when we

have very large or very complex objects. In general, .rda

files save and load more quickly because they are stored as

compressed code (in the form of

lists). Here is what it looks like:

save(otsego, file = "otsego.rda")When this kind of a data file is loaded back into the environment

(using load(file='otsego.rda'))’ it has the same name, but

is stored as a list. Dun, dun, dun…

Summarizing and visualizing data

Now that we have a handle on how R works, and how to get our data in and back out, let’s take a quick break and then we’ll spend some time to re-inforce data manipulation and wrap things up with some plotting!

Stay tuned!

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Data are provided for educational purposes only unless otherwise noted.